In the previous parshiyot we can see that there is an emphasis on the transition of the nation from the desert to the Land of Israel. This transition is also seen in the change of style of leadership-from a complete dependence on Moshe to the elders of the tribes- and from the change in leaders, ie the succession of Yehoshua. Therefore we should ask ourselves, why is the parshah of Nedarim (Vows) written specifically here as the Jewish people stand on the threshold to enter the land of Israel? Why did the Torah not place it near laws similar to it, such as the laws regarding a Nazir? How is the concept of vows related to the central theme of Bamidbar, which is the transition from Moshe and the generation of the Desert to the Land of Israel.

The Sefat Emet hints to us that this parshah is the beginning of the transition from the written Torah to the Oral Torah. The uniqueness of Nedarim from other mitzvoth is that other mitzvot are commanded on man by the Torah, and as such the commands come directly from Hashem. By Nedarim it is man who prohibits himself from certain actions, and yet these vows receive a status similar to biblically ordained prohibitions. The Parshah of Nedarim reveals to us that man can take the concept of Kedusha and import it on something which was originally unsacred. In other biblical laws we find some similarities, such as by the idea of Tosefet Shabbat (adding onto Shabbat) and Tosefet Yom HaKippurim (adding onto Yom Kippur), or by adding to the already existing section of the Temple by sanctifying new sections ect. Yet in all of these cases we merely extend pre-existing Kedushah, but we do not create it. By Nedarim, however, we completely change that which is unsacred into sacred with no pre-existing holiness. This itself is an Oral Law concept, and as such it becomes understandable why this law is placed in this parshah.

Part of the dependence of the Jewish People in the Desert was based on the idea that all spirituality was sent from God and that man has no ability to innovate. And while we know that there is a biblical prohibition to add or detract from the commandments (בל תגרע ובל תוסיף), we see that there is some ability for man to innovate. As such this innovation is symbolic of the Jewish People’s growth from the Desert to the Land of Israel, and from dependence to independence. Hence, if until now the nation received from Moshe all of its spiritual and physical needs, now we are transitioning into an era where each individual must supply himself with physical needs, such as food, and also with spiritual needs.

Rabbi Soloveitchik zt”l stated that this principle is true for everything which is Holy, ie that there is no meaning to Kedusha without human involvement. Just as man by Nedarim can impart Kedusha on the unholy, so too by Kedusha which was ordained from the Torah it is up to man to impart that holiness onto the world through action. There are several examples to this, such as Kiddush on Shabbat. Even though the holiness of Shabbat exists whether or not we do Kiddush, we are still commanded to sanctify Shabbat through doing Kiddush. In other words, despite that the holiness is ordained from Heaven there is still a desire that man partake in spreading its holiness. This is most noticeable by the ability of the Sanhedrin to decide the new months. The Sages learn that the ability of the Sanhedrin to decide the new months, and in consequence all of the Holidays, is binding even if they did so based on an intentional mistake. This idea is logical if you understand that there is an importance in having human involvement on some level.

This idea is especially important regarding Torah learning. Even though the Torah is from Heaven there are a vast amount of mitzvoth which were innovated and revealed through human involvement. This is stressed through the strength of logic in the Gemara (ברכת הנהניו נלמד מכוח סברא), and the thirteen principles with which the Torah is elucidated. Parallel to this it is important to recognize the other side of the coin, which is that all the Torah was given to Moshe at Sinai, and that we are not permitted to simply do as we wish. This balance is not just the key to learning the Torah, but to the transition of the Jewish People from the desert to the Land of Israel and from dependence to independence.

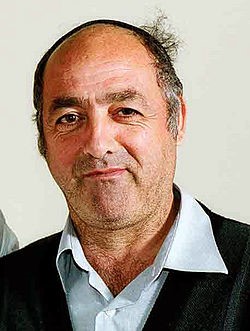

Rabbi Haim Sabato was born in Cairo, Egypt to a prestigious rabbinic family; he and his family made Aliyah in 1956 during the expulsion of Jews from Arab lands. He studied in Yehivat Hakotel, and in 1977, at age 24, he helped found Yeshivat HaHesder Birkat Moshe in Maale Adumim, Israel, and currently serves as one of its Roshei Yeshivah. Besides for his Torah scholarship, Rabbi Sabato is widely known as a popular author, and his novel “Adjusting Sights” (תיאום כוונות) won the Sapir Prize (akin to Israel’s Pulitzer Prize) in 2000.

Translated by RZA-Aryeh Fellow Nimrod Soll.