Why do we eat Maror on Pesach? Ostensibly, the answer to this question is so straightforward that it is not I who should be speaking about this, but my pre-school-age grandchild. Why is it so straightforward? Because it is one of the only cases in which the reason for the mitzvah was indicated by Halacha. In general, we do not bother much with reasons for mitzvot, and certainly not in the realm of Halacha. That is, we consider and debate them on philosophical grounds, but we do not determine them in normative law.

Yet, here it is said: “Whoever has not said these three things on Pesach has not fulfilled his obligation: Pesach, Matzah, and Maror….Why Maror? We eat Maror because the Egyptians made our forefathers’ lives bitter in Egypt.” Clearly, the answer to why we eat Maror on Pesach is already part of the Halachic corpus. If that is the case, I should not have asked the question, and once I did, I could have left it as merely rhetorical, because everyone knows why we eat Maror on Pesach.

The problem with this answer is that if you check it directly against the Torah text, it doesn’t correspond. The Torah speaks of eating the Korban Pesach with Matzah and Maror as a part of the celebration of redemption and salvation. And then to throw in Maror, as a symbol of bitterness, into the mix? Of course, the answer can be simply, yes. But that does not seem to be the simplest reading of the text.

I would not have dared say this had the Or HaChaim HaKadosh not made this very claim. The Or HaChaim HaKadosh said that as per the simplest understanding of the Torah text, we eat Maror on Pesach for one reason only: because it tastes good. Ask yourselves: When you go to buy shawarma, what is the conversation you have with the seller? The first thing he’ll ask you is, Pita or Lafa? The second, Do you want spicy sauce? That is exactly what is written in the verse, “And they shall eat the meat on this night, roasted, and Matzot (pita or lafa) on Maror (bitter, spicy herbs) they shall eat it” (Exodus 12:8). In the words of the Or HaChaim HaKadosh: “For it is the way of all who eat meat to eat it with a spicy food because it gives the palate a pleasant sensation.” This is truly the simplest reading of the text.

However, it contradicts the Halacha we quoted above. The Halacha is that Maror is eaten because the Egyptians embittered our lives. I once heard a wonderful explanation from Rav Broyer of blessed memory, which I believe can serve as a guide for life. He said the following: The Maror, when taken by itself, is bitter. As in the Halacha, “Because the Egyptians embittered our lives.” Normal people, especially from my background, do not eat spicy sauce or dip by the tablespoon. But when this Maror is a part of the sandwich of roasted meat and Matzot, it gives the meat a distinct and special flavor. Similarly, suffering on its own is bad, simply put. Exile, subjugation, and pain are bitter and awful. But when you see your life as a totality, you see that the difficult times, the difficult days, the subjugation, the mishaps – all give life its flavor, give it a singular meaning. They are part of creation, not just destruction. And they are part of the solution, not just part of the problem.

This is the way we relate to pain and suffering. Suffering is not beloved onto us. As all the Amoraim say at the beginning of Shas, “not it [suffering] nor its reward.” But when suffering does come upon us, we know to remember all the difficulties they comprised, on the one hand. And on the other, that same suffering, when viewed in the context of a greater process, is what elevates us to a new stratum of life. It grants our lives a meaning that would not have existed without it.

Therefore, on Pesach we eat Maror because it is bitter and painful, yet we are able to see it as part of a greater whole, as those who eat meat with a spicy sauce, because it gives it a pleasant taste.

This is suffering, this is pain, and this is the all-encompassing totality that we are able to see on Seder night.

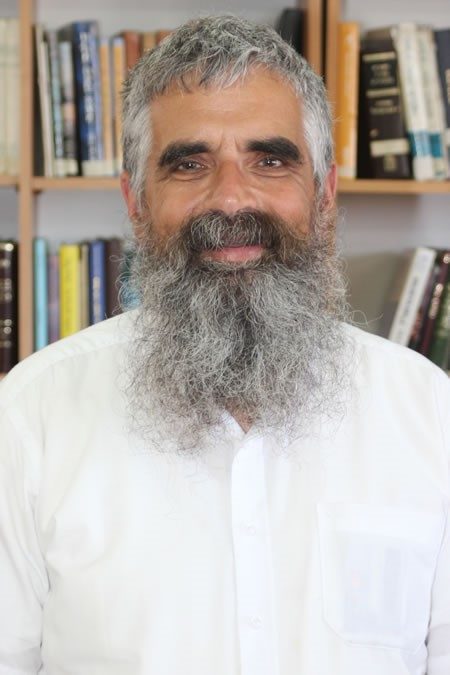

Rav Yuval Cherlow is the head of Yeshivat haHesder Petach Tikva, which changed its name and location to Yeshivat haHesder Ra’anana, also known as Orot Shaul. Rav Cherlow has published numerous articles and lectures on the internet and has answered more than 70,000 questions about Jewish thought and practice on his online forum “Ask the Rabbi.” Rav Cherlow was also one of the founders of Tzohar, a forum that bridges the world of the rabbinate with the wider Israeli public. He has served in many societal roles, including writing position papers for the Knesset concerning religious matters, as well as taking part in the creation of certain laws, such as one regarding testing medications on humans. Rav Cherlow is a sought-after speaker by both the religious and the secular public, speaking at universities all over Israel, as well as in rabbinical forums. In 1997, he received the Minister of Education’s prize for Torah creation.

Translated by Yehudith Dashevsky