The book of Vayikra is the book of Kedusha, Holiness. Generally when we speak of kedushah, we deal with two main subjects: Prohibited foods (מאכלות אסורים) and Prohibited Relations (עריות). However, the book of Vayikra also includes other categories of kedushah-the kedushah of a place (via sacrifices, korbanot), the kedushah of time (Holidays, Moadim), the kedushah of the Land of Israel (Shemittah and Yovel) and the kedushah of the Jewish People (Brit Milah).

But even more than these there is also the kedushah of the society of Israel. One who looks in this week’s parshah will see many societal laws, and first among them is the unique command of “Love your neighbor as yourself” (“וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָּמוֹךָ” [ויקרא יט, יח) along with “You shall be holy, for am I Hashem your God” (קְדֹשִׁים תִּהְיוּ כִּי קָדוֹשׁ אֲנִי ה’ אֱלֹקיכֶם) and “You shall become sanctified and you shall be holy, because I am Hashem your God” ( והתקדשתם והייתם קדושים כי אני ה אלוקיכם). Yet, at first glance we must ask, what do these commands have with kedushah?

In order to better understand this we need to explain the concept of kedushah, which is separation through self-restraint. That which separates between Israel and the nations is the demand that Israel have self-restraint. In the past, idolatry was all about excessiveness; excessiveness in eating and excessiveness in intimate relations. Every idolatrous sacrifice was accompanied by wild feasts that included drunkenness, excessive eating and public prostitution. When the Torah speaks of worshipping God with holiness it demands not excessiveness but restraint and moderation. The Service of God demands restraint in our physical lives in order to grow in our spiritual lives as well.

We need to clearly understand how revolutionary this idea of kedushah, holiness, in a society is. In most countries throughout the world, Idealism is not part of the law of the land. There is no law which requires individuals to believe in ideals, laws usually are there to prevent/deter you from harming others and not to help them. Consequently, most societal laws do not sprout from ideals of holiness but from the hope of keeping law and order. In Torah Law, however, societal laws aren’t there to simply stop you from harming others. Torah Law demands that Jewish society be above the normal society and that it not only seek to maintain law and order but holiness as well. Therefore, the Torah demands us to lover our fellow Jews as we love ourselves, and even forbids us from holding grudges and hatred towards other Jews. No law in any of the Western democracies forbids individuals from hating other individuals in their hearts, only from physically or verbally hurting them. The Torah, however, does. “You shall not hate your brother in your heart” (לא תשנא את אחיך בלבבך ויקרא יט, יז), and “You shall not take revenge and you shall not bear a grudge against the members of your people” ( לא תקום ולא תטור את בני עמך ויקרא יט,יח). Jewish society is required to be more than just “law and order”; it must also have a concept of holiness, kedushah.

A clear example of holiness in a Jewish society can be seen from the prohibition to curse a deaf man. The Rambam in Sefer HaMitzvot wonders why the Torah prohibits such an act. For in the end of the day the man who is deaf cannot hear your curse, and therefore, was not offended. Yet that exactly is the answer. Even though no one was offended, Jewish society must be more than law and order and the maintenance of peace, it must be sacred and holy. One who curses his fellow man, even if his fellow man was not offended, has violated that sanctity. According to this it becomes clearer as to why the Torah commands us to love our fellow Jews as we love ourselves, for the commandments aren’t there only to create law and order but holiness, kedushah.

The novelty in Vayikra is that these societal laws appear in the midst of parshat Kedoshim, in the heart of the book of Vayikra, the Book of Kedushah. Moreover, the Torah directs us individuals as to how to reach this level of societal holiness. If one fights with himself to act in a certain way, then sometimes he will fail and sometimes he will succeed. But if we enter this test through the prism of kedushah, then it becomes a lot easier, for why would I want to do an act that contradicts what I am? When one understands and internalizes the concept of kedushah he is far more capable to live a life of kedushah and help create a holy society.

Thus, the Torah tells us that if one acts with restraint in his life and not with excessiveness, then one reaches this level of holiness. This is in contradiction to many other religions which tend to choose one of the extremes, either to completely submerge in physicality and disregard the spiritual or to immerse in spirituality and completely ignore the physical. The Torah states that both are wrong, and both negate the concept of kedushah. One needs spirituality as well as physicality, but it reminds us that there must be self-restraint, and this is derived from the idealism of the fact that man was created in the image of Hashem and that the Jewish People are Hashem’s Chosen Nation.

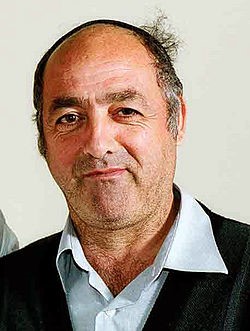

Rabbi Haim Sabato was born in Cairo, Egypt to a prestigious rabbinic family; he and his family made Aliyah in 1956 during the expulsion of Jews from Arab lands. He studied in Yehivat Hakotel, and in 1977, at age 24, he helped found Yeshivat HaHesder Birkat Moshe in Maale Adumim, Israel, and currently serves as one of its Roshei Yeshivah. Besides for his Torah scholarship, Rabbi Sabato is widely known as a popular author, and his novel “Adjusting Sights” (תיאום כוונות) won the Sapir Prize (akin to Israel’s Pulitzer Prize) in 2000.